Vietnam at the Gate of TPP – A Strategy Perspective

Xin vui lòng tải bản tiếng Việt tại đây

Vietnam at the Gate of TPP – A Strategy Perspective

TPP was one of the most spoken buzzwords within Vietnam’s business circle in 2015. As the nation with the lowest level of income among the members, Vietnam is said to benefit the most while at the same time face the greatest hurdles if it wants to truly integrate into such a comprehensive economic agreement. There have been much discussions in the press about shifting production bases, rules of origins or necessary reforms of SOEs but we believe these content while being too broad are not detailed and relevant enough for business managers. This short article will attempt to summarize TPP’s key points, outline where Vietnam stands at the moment, and presents key insights regarding TPP and other FTAs that we believe businesses managers will find useful in their strategy planning.

Note: Countries are abbreviated and sorted as follows: CA: Canada, US: United States, ME: Mexico, CL: Chile, PE: Peru, JP: Japan, VN: Vietnam, SI: Singapore, BR: Brunei, MA: Malaysia, AU: Australia, NZ: New Zealand.

- What is TPP?

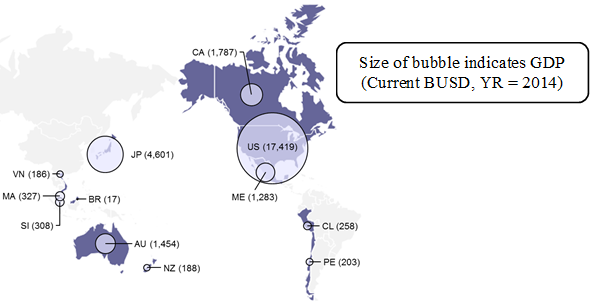

TPP is a free-trade agreement (FTA) involving 12 countries (Canada, United States, Mexico, Peru, Chile, Japan, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, Australia, New Zealand), more than 11% of world population and nearly 40% of world GDP.

The most important thing to note about the participating countries is that they are on the rim of the Pacific Ocean, hence sea trade through this route will be a key element of the partnership. China is not a part of TPP, while Korea and other ASEAN nations such as Thailand have expressed their intent to join. As the U.S. is clearly the leader in terms of absolute economic power, TPP is often cited as the counter-agreement to RECP which China leads.

Figure 1: Location and GDP of TPP members

Source: World Bank (WB)

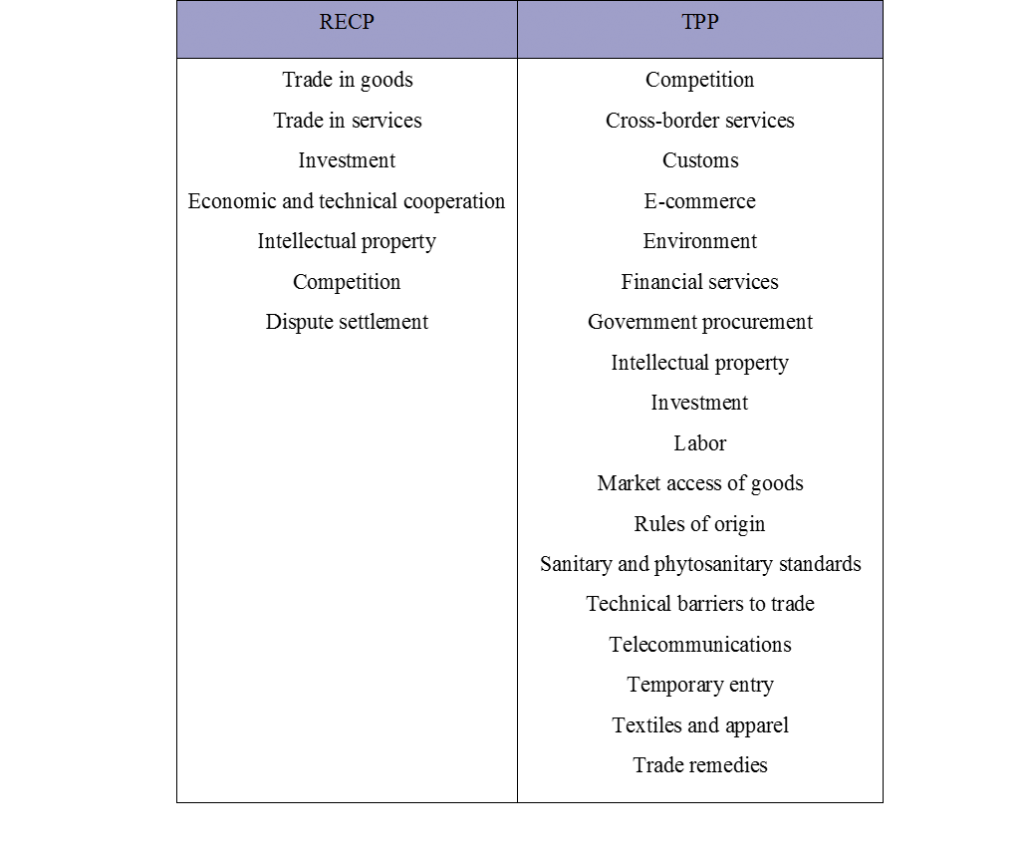

In terms of content, TPP’s 30 chapters sets one of the highest standards both in terms of breadth of topics covered and stringency of commitment, clearly outdoing the Chinese-led RECP.

Figure 2: Comparison of scope of RECP and TPP

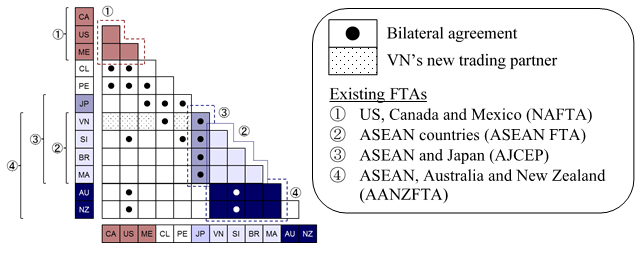

In spite of its enormous scope, TPP is just another free-trade agreement (FTA). In fact, many of the provisions agreed to in TPP have been covered by previous bilateral and multilateral FTAs, as seen below. In particular, for Vietnam the truly new trading partners are NAFTA members and Peru. Within this geography, The U.S. is the most prominent give its large market size, however Canada is also promising given Vietnam’s current low export levels.

Figure 3: Existing trade agreements between TPP members

Sources: Each TPP member’s Ministry of Commerce’s website, secondary research

The conclusion from the chart above is that business managers must make decisions based not only on TPP conditions but holistically within the context of all FTA agreements covering the concerned markets.

- Where does Vietnam stand?

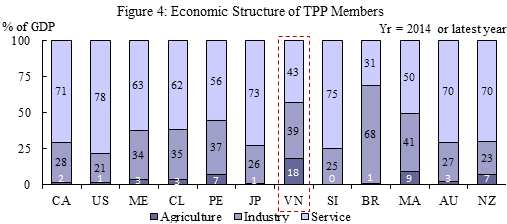

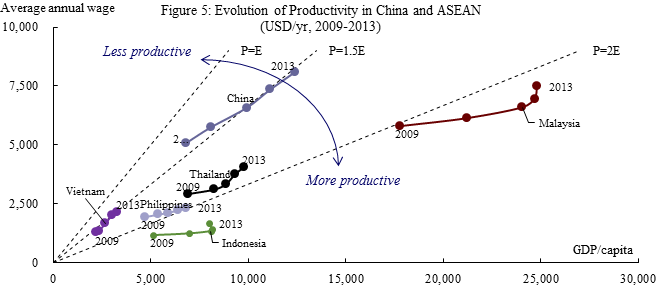

Vietnam is the most agriculturally-oriented nation within TPP. At the same time, low levels of productivity caused by an underdeveloped supporting industry, lack of R&D hubs and skilled labor prevents Vietnam from moving up the supply chain into higher value-added manufacturing and services compared to its peers in the region.

Sources: Vietnam’s customs, CDI’s adjustments

Sources: International Labor Organization (ILO), Asian Productivity Organization (APO)

Productivity = GDP/per capita divided by average annual wage. A nation is considered more productivity if it earns more and more in GDP/capita for the same dollar in average annual wage.

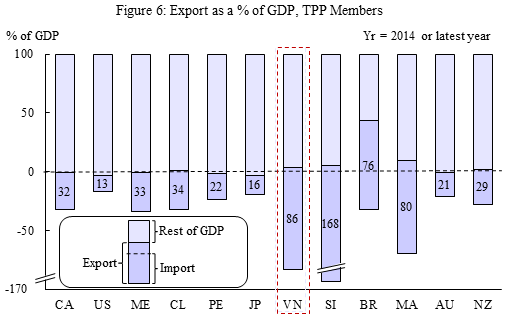

Exports play a dominant role in Vietnam’s economy. In fact, among TPP members, Vietnam’s export percentage of GDP is second only to that of Singapore. As such, there is much expectation that that TPP would bring a huge export boost to Vietnam’s economy.

Sources: WB, Vietnam’s customs, press releases

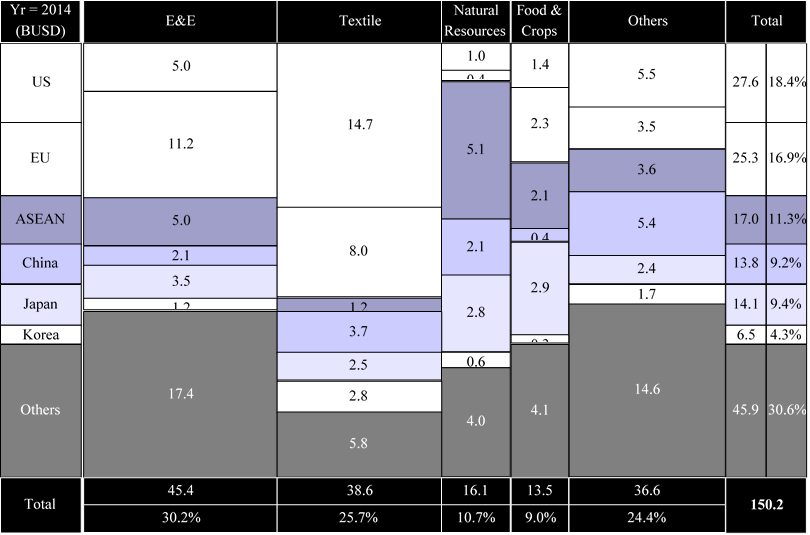

Looking at Vietnam’s major export product groups, we see that food and crops contribute a significant amount to the total export value, however this category is still minor amount compared to textile products (Vietnam’s so-called export champion), and electric and electronic equipment (E&E), mainly thanks to enormous investments in the last category in recent years by Samsung, LG, etc.

Looking at export destinations, we see the US and EU are the two largest markets, accounting for over half of Vietnam’s exports. While the EU is not covered under TPP, a separate agreement between EU and Vietnam is under way. As such, in order effectively utilize all preferential tariff treatment, businesses must monitor the trade liberalization progress as a whole outside of the TPP context.

Figure 7: Vietnam’s Export by Destination and Product Group

Sources: Vietnam’s customs, CDI’s adjustments

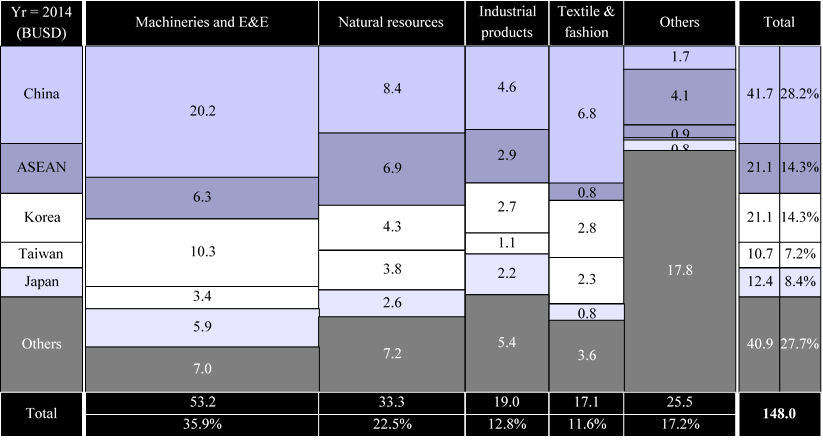

On the import side, China single-handedly supplies nearly 30% all of Vietnam’s import needs. In particular, it is a source of machineries, E&E and textile material supply feeding into Vietnam’s finished goods. The importance to note is that since China is not part of the TPP, industries that rely heavily on Chinese imports face stringent conditions called forth by the so-called rule of origin. In the case of textiles, TPP demands that textile materials from yarn forward must be manufactured in the exporting country order for it to benefit from favorable tariff treatments.

Figure 8: Vietnam’s Import by Source and Product Group

Sources: Vietnam’s customs, CDI’s adjustments

- Strategy Perspective for Managers

With so many different angles to consider and rules to remember, what should business managers keep in mind to make the best of FTAs in general and TPP in particular? In this final section, we highlight four key takeaways that are essential for any businesses operating in Vietnam as they attempt to incorporate TPP/FTAs into their strategic planning.

a. Legal Intelligence

As many complex and overlapping FTAs are in development, it is very important for managers to keep track of current and future rules, quantify the impact on their business, and make use of the applicable regulations to their fullest. One common misunderstanding is that FTAs in general and TPP in particular are only about tariffs. In reality, other conditions such as the tariff reduction schedule over time, quotas (if any), anti-dumping regulations, technical barriers, health & safety barriers, etc. may open up or restrict an entire market from the reach of the company.

In particular, large enterprises are advised to form an in-house legal team. This is because with more export destinations, the risk and complexity of legal disputes increase, while legal intelligence (i.e. a fixed cost) can be spread out over a larger export volume. As for SMEs, they should frequently update with trade authorities and industry associations for useful (and often free) information.

b. Economy of Scale

A trend that typically arises when markets integrate is the emergence of large players that fulfill a very specific role within the supply chain of their industry but on a global scale. These players have multiple plants, employ tens of thousands of employees, and have invested in specialized technology, manufacturing processes and a well-trained labor pool that are capable of taking large and complex orders from multiple top-tier clients.

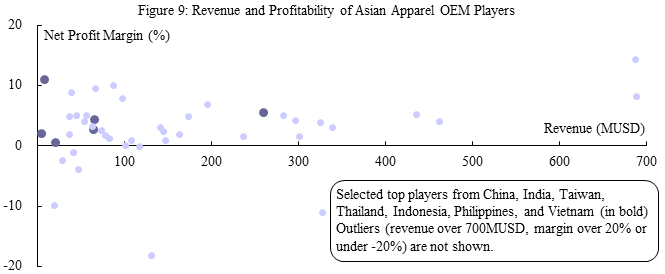

In the graph below, we show the revenue and profit margin of major apparel OEM players across Asia. Vietnamese companies (in bold) enjoy a profitability level comparable to their peers, however with the exception of the industry leader Viet Tien, remaining players are typical small in size. This has created major difficulties for these players as trade barriers lower and world markets becomes a level playing field, where players with better economy of scale often emerge victorious.

Source: SPEEDA

As such, local businesses when integrating into the world’s supply chain should be aware of their economy of scale vis-à-vis global competitors. Lack of scale can be compensated through collaboration with other local players in the short run, growth through M&A activities in the long run, or bypassed altogether by employing a differentiation strategy where scale is less important or made irrelevant by developing other advantages and capabilities (see takeaways c. and d. below).

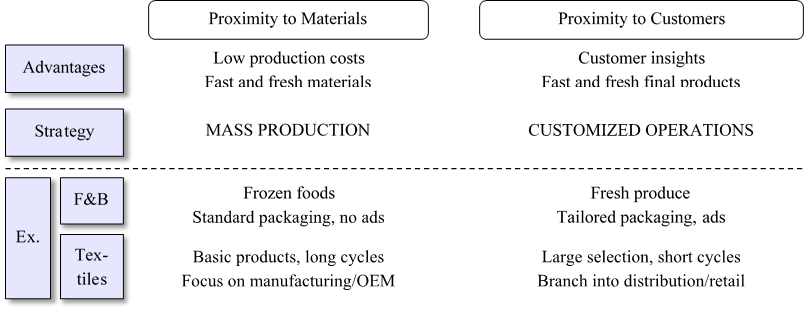

c. Proximity to Customers

As mentioned above, when import tariffs are removed, multinational companies can leverage their global presence to position R&D, production and sales in strategic locations (outside of Vietnam) for optimized supply chain and economy of scale. To compete, businesses serving the Vietnamese domestic market can alter their operations to benefit from proximity to customers, and advantage that an export-based foreign competitor does not have.

Figure 10: Proximity to Materials vs. Proximity to Customers

Let’s take the example of two industries: food and beverages (F&B) and textiles. In the F&B industry, recently there has been a surge of Thai processed food exported to Vietnam thanks to efforts of Thai retailers / distributors. While these products may earn the trust of the Vietnamese consumers (“cheaper than Japanese products but safer than Chinese products”), they suffer a couple of drawbacks due to the lack of the manufacturer’s presence in Vietnam. The package is unchanged (written in Thai), the ingredients are not native to Vietnamese tastes, and there is no way for consumers to know about the product except by going to store. A Vietnamese competitor may take advantage this by investing in marketing: design attractive packages, launch advertising campaigns, and monitor customer responses.

In the textiles industry, a similar story takes place where Chinese clothing items flood the Vietnamese market. These products are often very cheap, with the drawback of being very poor in style / size variety and not a complete good fit for Vietnam’s climate. A Vietnamese textile player may decide to leverage its proximity to customers by venturing into retail to capture more added value, as well as launching a large selection of items to gauge the customer response. Through continuous monitoring of sales levels, it could quickly phase out low-performing items and boost high-performing ones, thereby negating competition from Chinese exports. In fact, this is the strategy (also called “fast fashion”) is what made Zara one of the most successful fashion retailers today.

d. Parameter Mapping

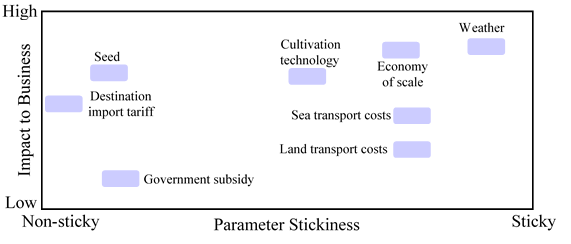

Over the long-run, advantages such as economy of scale, proximity to customers, etc. are parameters inherent to a given industry. These parameters can be mapped based on their impact to the business (quantitatively in revenue or unit price) and their stickiness (qualitatively based on the difficulty in building / imitating an advantage corresponding to each parameter). For the sake of illustration, we map out key parameters for a hypothetical Vietnamese agricultural export in Figure 11-A below.

Figure 11-A: Industry Parameters

Agricultural Product

Source: CDI’s hypothesis

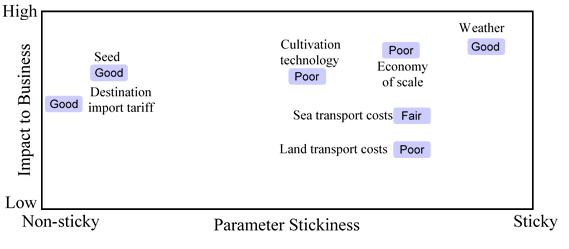

For example, weather is an extremely important parameter in that it may make or break the cultivation schedule. A player with a weather advantage can rest assured that it cannot be easily copied in the future by other players. In figure 11-B below, we hypothetically evaluate the advantages that a certain Vietnamese exporter has / does not have over a Chinese competitor for such parameters, giving a “Good”, “Fair” or “Poor” assessment of the former’s position over that of the latter.

Figure 11-B: Advantage Evaluation

Vietnamese Company X vs. Chinese Competitor Y

Source: CDI’s hypothesis

With such mapping, business managers can prioritize which parameters to focus on in their strategy planning. High-impact advantages are more important yet sticky ones should require fewer resources to maintain. On the other hand, high-impact disadvantages require investments so that the business catches up with its competitors, yet sticky disadvantages present a dilemma to business managers: invest heavily (when such is an option) or give up entirely and focus on building up other advantages.

In our example above, cultivation technology (currently a disadvantage for the Vietnamese player) is highly impactful and should be improved through cooperation with a foreign partner possessing such technology. By contrast, the import tariff at the destination country is an advantage as this country and Vietnam are TPP members. However, this advantage is non-sticky, as China is also negotiating a bilateral agreement covering this product group with the said country. As such, business managers should not count too much on this advantage as it may nullified shortly, and instead must make sure they are not neglecting other important capabilities.

May 2016

Corporate Directions (Vietnam)

Consultant, Pham Le Duc

Download attachments

Download attachments