The Thai market to watch and their players -Cosmetics market-

The Thai market to watch and their players

Cosmetics market

We at CDI-Thailand discuss the various socioeconomic issues of Thailand and ASEAN related to Thailand’s noteworthy market and its players. In this article we would like to discuss the rapidly growing cosmetics market.

The high growth of cosmetics market despite political instability and economic downturn

As you know, in the last few years Thailand has gone through several major adversities. Thailand suffered a blow to the agriculture and automotive industry after the 2011 floods; there was the 2013 occupation of central Bangkok, as well as large-scale demonstrations that eventually led to a coup in 2014. Though the coup’s aim was to stabilize the country, a transition into a military government has negatively impacted the tourism industry. Thailand is in a difficult political and economic situation and it does not look to be improving much any time soon.

As a matter of fact, Thailand’s GDP growth in 2014 was a measly 0.71%, with a negative growth rate of -2.33% after the global recession in 2009 and -0.08% after the 2011 floods, giving us the worst levels of GDP growth this century. Despite the government’s expectation of the 2015 growth to recover to a “cruising speed” of around 3.5 – 4%, the situation in Thailand both domestically and internationally hasn’t changed much, and at this point we cannot yet be optimistic with Thailand’s outlook.

However, even during this time the city of Bangkok – especially the young – are in good spirits. Despite the temporary disorder that follows natural disasters and political strife, the Thai people quickly returned to their everyday life. Roads are overflowing with traffic as always, and shopping malls are prospering as a result of continuous developments and renovations. The young high-income and middle class who commute to central Bangkok everyday appear to have a desire to consume that is as high as ever.

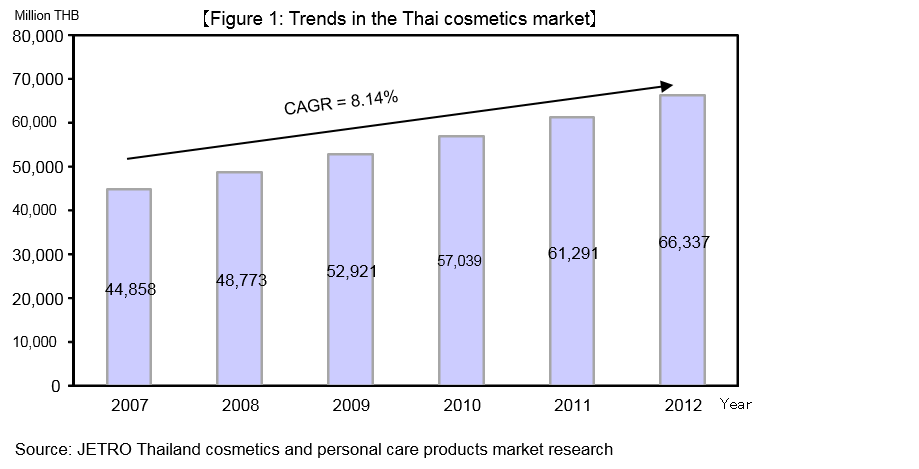

The central topic to our article – cosmetics – can be said to symbolize this trend. The market size of the Thai cosmetics market was at THB 44.8 billion in 2007, and five years later it is at THB 66.8 billion – a growth of 48%. Despite the economic and social disorder in the period, the market had enjoyed consistent annual growth of over 8% (figure 1)

The changes in “Thai Beauty” that reflects this period

With the overabundance of fashion magazines in shops in the premises of elevated railways (BTS), or the various eye-catching advertisements downtown one can clearly see the high level of interest that Thai women have on beauty.

In fact, after having asked the Thai women around the author, we found they spend up to 20% of their monthly salary on beauty products. Though this expenditure is not a monthly one it is not unusual to occur a few times a year (every 3-4 months). According to Hakuhodo report in 2012 (admittedly a fairly dated article), “beauty-consciousness of Asian women from a survey of 14 cities”, East Asian women (including Japanese and Chinese) has a strong preference towards skincare products (toners, milky lotions, liquid foundations and creams), while women of Southeast Asia are more oriented towards makeups such as lipsticks, (face) powders, and foundations. Among them Bangkok has a very high usage level of skincare and makeup products of around 85% of female population (matched only by Singapore). It appears to be characteristic of a Thai woman to have a very strong tendency to “care about their skin” compared to those from other countries in Southeast Asia.

However, the phenomenon of Thai women caring about their outward appearance and enjoying the use of cosmetics is a relatively recent occurrence. Until the 1990s the Thai cosmetics market was dominated by luxury cosmetic brands from Europe and Japan sold in shopping malls. Though many may have longed for them, they were anything but affordable. After the turn of the millennium however, Korean-made cosmetics –taking advantage of the popularity of Korean TV series – made an appearance in the Thai market. Their relative affordability and good quality created an environment where young women of middle-income are now able to obtain the cosmetics they wanted.

At the same time, the usage of social media such as Facebook and Line became widespread. A new range of consumer movements such as the sharing of “selfies” online and cosmetics reviews by popular bloggers became widespread.

As a result, those who were formerly indifferent about their outward appearance began paying more attention, and the interest in cosmetic products surged.

Additionally buzz marketing websites emerged and websites such as Jeban.com is now the largest online Thai community for women with over 830,000 members. In such a website, bloggers shared cosmetic reviews through the Jeban Facebook fan page and Instagram to the public, gaining massive popularity. Cosme.net (website managed by a Japanese buzz marketing company) has over 240,000 members, and they are used widely as a PR tool for cosmetic companies.

According to JETRO’s president Wakai in an interview, the demands within the Thai cosmetics market are heavily influenced by the teenage years of each respective age group. Those over 40s prefer the “full makeup” with a western style and brands, those in their 30s follow the Japanese-style “natural makeup”. Those in their 20s are favouring the Korean-style, while the current under-20s are being influenced by the Japanese-Korean hybrid, which is currently emerging.

Aside from the above-mentioned reasons for growth, the Thai cosmetics market is also affected by “the increase in attention to cost performance and consumers’ low brand loyalty” and “the expansion of the men’s skincare market”. And as a result of FTA coming into effect, export and import duties within the ASEAN region are abolished, resulting in businesses entering the market with vigour.

The market’s driving force: the specialist stores’ battle over the middle-class

Reflecting upon the history of the market’s formation, the presence of domestic cosmetics manufacturers were rather insignificant.

Imported brands dominate the luxury goods market, being sold in various department stores (the so-called “counselling products”). The products currently spearheading the activity in the cosmetics market (the so-called “self-products”) are those aimed towards the middle class. Instead of a “brand name” product, it appears that private labels (or private brands, PB) – original brands made for retail stores – are more typical.

That is, the leading retail businesses designs and develops several concepts for their chain and private brands (PB), and those selected are then distributed to their regular distribution channels.

While each retail store chains sells PBs as well as Japanese and Korean products, cosmetics manufacturers in Thailand are profitable by simply being ODMs, which differs to the situation in Japan. For this article we will focus on the competition between the independent specialist shops that enjoyed remarkable growth within the middle-class market, and the drug store chains that made a striking entrance into the market.

*Counselling-products – products that are sold in cosmetic areas in department stores, where the employees have specialized knowledge of their brand and provide guidance to their (luxury) product lines and choices.

*Self-products – products sold in drugstores, where there are a wide variety of cosmetics sold in one place, without an employee for each product brand.

【Example 1: SSUP, a veteran specialist with a vision for the foreign market】

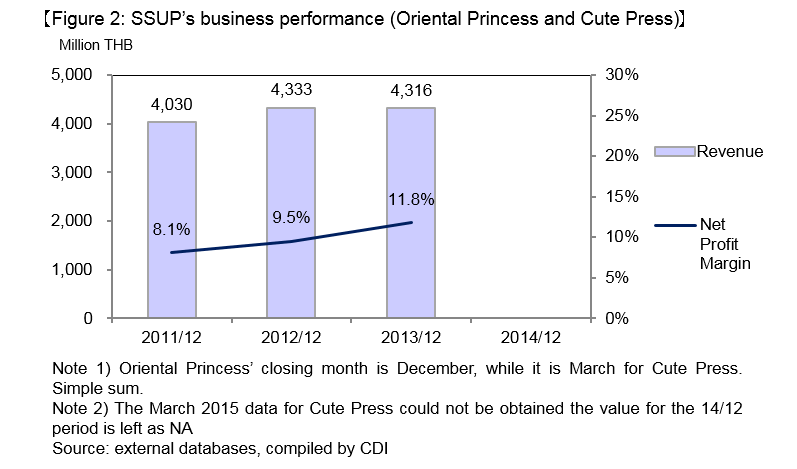

Thailand’s local specialist chain stores made an appearance within the “self-products” market back in the 1970s, of which SSUP is one of the most successful. Domestically, the “Cute Press” brand is sold in 240 stores, “Oriental Princess” brand is sold in 300 stores. “Cute Press” was introduced in 1976 and have widely spread, being sold primarily within stores on the streets of downtown. With their products sold in 200 stores in other ASEAN countries, SSUP is certainly not losing traction in terms of growth. “Oriental Princess” brand, introduced in 1990 in response to the rising income levels, targets a high-end group of consumers. The Oriental Princess brand is effectively segregated with the Cute Press brand despite being sold in the same shopping malls.

【Example 2: BEAUTY’s rapid growth through the “loved by the youth” concept】

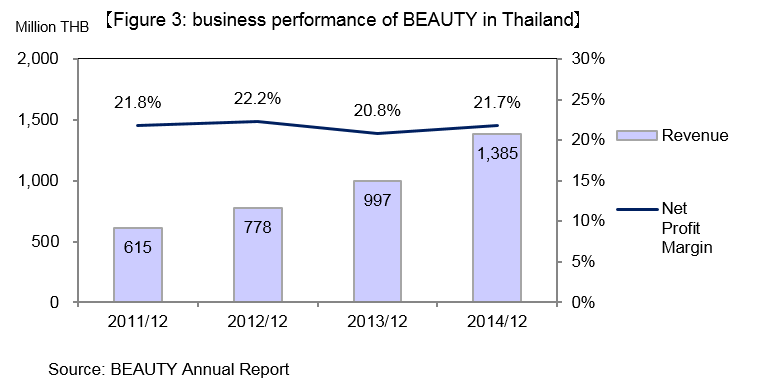

Accompanying the rapid growth in the market, a relatively recent start-up company has been quite successful and is now listed on the Thai stock exchange. Established in 2000 and listed in 2012, BEAUTY group is an influential Thai chain store with the biggest momentum at the moment.

BEAUTY BUFFET, being sold in 240 stores are being sold with young consumers as the target audience. As the name “buffet” implies they have consolidated designs of billboards, shops and product lines that gives an image of casual restaurants, which is well received by the consumers. In the same manner, “BEAUTY MARKET” utilizes the concept of supermarkets and provides an abundance of product selections; while also having a “BEAUTY COTTAGE” product line that uses natural ingredients and sold in a vintage style.

BEAUTY utilizes a strategy with multiple brands and product lines in which each store focuses on one product line, so that different stores can meet the consumers’ various needs. Of those brands, the MADE IN NATURE series and Girly Girl series within the “BEAUTY COTTAGE” product lines are highly rated; it is also being sold wholesale to supermarkets and convenient stores.

As a common feature across the brands, there is an abundance of product variations with low prices, which you can try out, as well as a point system in which points can be used to obtain newly released products or get a discount. By following the way of thinking that having a solid infrastructure is the best approach for retailers, they can match the young consumers, their main target (those without a lot of disposable income).

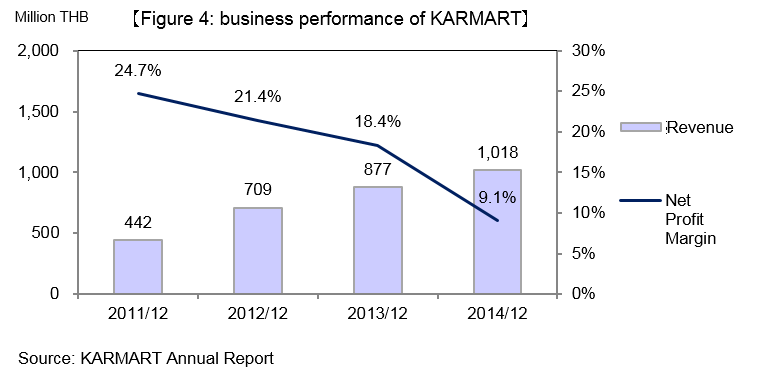

Though the market may be growing rapidly, it is not so easy that you can expect to gain more profits by simply producing more and expecting sales to match. In fact another company – KARMAT – that entered the market around the same period as the BEAUTY group has a different story altogether. KARMAT is a chain that focused on Korean-oriented products, stores and advertising, growing rapidly during the influx of South Korean pop culture at the time of its establishment. However, an attempt at diversification after being listed on the stock exchange led to a sudden drop in profits, despite higher sales. With the fickle young consumers as the target market, the intense competition in brand establishment can be seen as the tough side of the market.

Thailand’s major conglomerates and Japanese companies take up the challenge; a movement to develop drug store channels

While a chain of independent specialists are stirring up the market as above, in Japan the situation is somewhat different for the drugstore chain – the other leading actor in “self-products’” distribution.

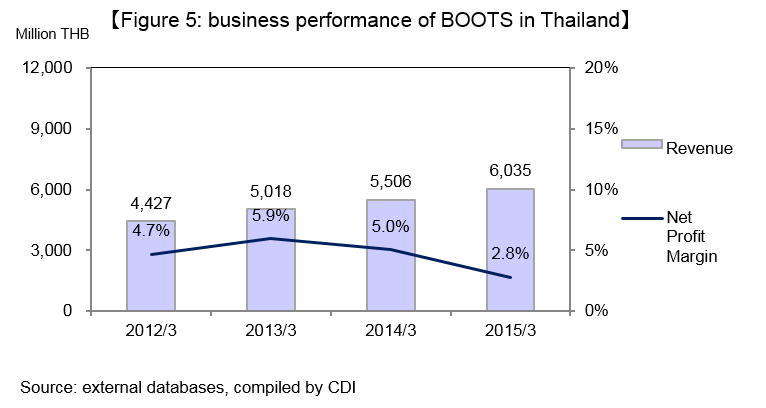

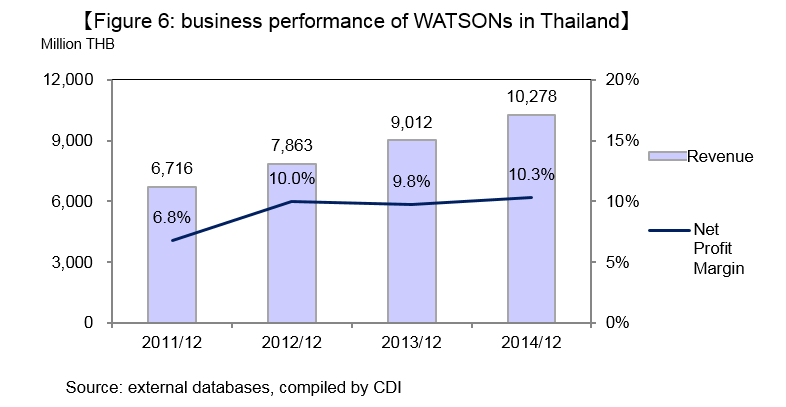

If one were to talk about drugstore chains in Thailand, Watson’s and Boots would be the first two that comes to mind, as the multinational chains that have dominated the market for a long time. Watson is Asia’s largest chain from Hong Kong with 260 stores in Thailand, and Boots is an English chain with 180 stores in Thailand. For Thai people, their image of a drugstore is a place to obtain “medicine and health foods, daily sundries and beverages”, and perhaps basic cosmetics such as lotions and creams; they are not really seen as a place to obtain self-products.

Lately however, there are movements one after another into the drugstore market, centred around major conglomerates in Thailand. In 2012 Saha Group teamed up to develop stores with Tsuruha and in 2014 Central Group did the same with Matsumoto Kiyoshi. There are movements to bring Japanese-style drugstores into Thailand that sells general medicine, heath foods and beverages as well as cosmetics and other daily necessities, by teaming up with Japanese drugstore chains. The primary reasons of this movement: poor growth potentials in the domestic Japanese market and the need to begin expanding overseas in earnest by Japanese drugstore chains probably need not be mentioned.

Tsuruha created a business partnership with Saha Group in 2010, performing market research with the prerequisite of production and sales of its own PB within Thailand and an entry into SEA. In November 2011 a subsidiary company of the joint venture Tsuruha Thailand is established, and in July 2012 the first overseas store in the Thai market is opened in a downtown shopping mall. They expanded to 16 stores by 2014 with future plans to open stores in Myanmar and Vietnam.

Matsumoto Kiyoshi, in addition to opening its own stores, installed “MatsuKiyo” areas within Tops supermarket (part of Central Group), and sells its own PBs, competing with CP Group (which has developed its own drugstore chain Exta within Seven Elevens) in mind. At the moment the efforts of the two companies appear to be favourably received by the consumers. From the authors’ acquaintances we are told, “we can obtain Japanese makeup and skincare products that are more affordable than western products”, “we can trust in the quality of those products as they are used by the Japanese” and so on.

Even so the challenges that the Japanese chains face is only beginning; it is currently unknown if they would be able to maintain its grip on the Thai market in the same way as Oriental Princess or Watsons.

Thai customers tend to be loyal to “house” brand products (PB) through the recognition and trust in the brands, created through the “billboard effect” during the stores’ development. Though the Japanese chains are adept at selling “name” brands they are not used to selling private “house” brands. It is unknown how effective the Japanese know-how would be in those situations, especially because Thai’s youth are not in the habit of buying cosmetics from drugstores in the first place. Japanese companies face the challenge of making their products more appealing. After the initial momentum created by their entrance into the market has passed, they will face many obstacles to success, even with the backings of major Thai conglomerates.

In order for these companies to secure future growth they should not try to force the Japanese method of doing business in Thailand nor should they emulate the store brands done by the local specialized manufacturers. They should attempt to give Thai consumers “the enjoyment of choosing a brand” and “the convenience of a one-stop service” through the provision of a range of higher-quality products than the incumbents as a new type of business, and increase the company’s brand awareness. At the same time, they should actively include the “house” brands (PB) cultivated by the local chain stores as necessary.

Furthermore, even while cultivating the Thai market; it is important to have a tangible plan of expansion towards ASEAN countries in mind. In addition to the FTA that came into effect, there is the mitigation of import provisions within the AEC after 2015, making it even easier to expand Thai-made cosmetics into the ASEAN market; generally the Thai cosmetics industry (both manufacturers and retailers) have the intention to actively expand to the ASEAN market.

The Thai market, along with Singaporean market is among the most mature. With an intense price competition in Thailand’s self-products market the products’ price and quality are more than adequately refined. The growth model in which the retailer chains who survived the fierce competition in the Thai market expand towards ASEAN is a reasonable one. Usually the leading chain stores that have been established up to this point have built up a network of stores within the ASEAN market that is comparable to their domestic market itself.

The fact that Thailand’s major conglomerates – that have a large network – teamed up with Japanese chain stores with this timing likely means that they are targeting the ASEAN market as a whole. In crossing over the Japanese market with a declining population the Japanese drugstore chains are facing tough new challenges; we can only pray for the success of those companies.

<Authors>

Takubo Nobuo CDI Partner

Kosugi Yuichi CDI Manager

Decha Koveampairoj CDI-Thailand Consultant

Prawarpa Kittikrairat CDI-Thailand Consultant

Download attachments

Download attachments